1 A rough approximation can be obtained by dividing those 703 places wherein a different reading is listed in the index to Ibn Mujāhid’s

Kitāb al-sab’ah fī al-qirā’āt by the total number of words in the Qur’an (surpassing 77,400), in order to arrive at 0.9% of words with an alternative reading. For these numbers see Yasin Dutton, “Orality, Literacy and the ‘Seven Aḥruf’ Hadith,”

Journal of Islamic Studies 23, no. 1 (2012): 10.

2 The early scholar from Baghdad, Ibn Mujāhid (d. 324 AH) is famous for enumerating seven acceptable modes of recitation in his work

Kitab al-sabʿah fi al-qirāʾāt. He selected those readings that had become widely accepted, picking one reader for every major center of knowledge in the Muslim world (Mecca—Ibn Kathīr, Damascus—Ibn ʿĀmir, Basrah—Abū ʿAmr, Madinah—Nāfiʿ) except for Kūfah, from which he chose three reciters (ʿĀṣim, Ḥamzah, al-Kisāʾī). There were many readings that were left out; for instance, Ibn al-Jazarī (d. 833 AH) stated that the early scholar Abū ʿUbayd al-Qāsim ibn Sallām (d. 224 AH) compiled twenty-five

qirā’āt. Some scholars, including Ibn al-Jazarī, took the list of seven from Ibn Mujāhid and added three other reciters to form the canonical list of ten: Abū Ja’far from Madinah, Yaʿqūb from Baṣrah, and Khalaf from Kūfah.

3 Both Muhammad Mustafa Al-Aʿzami and Yasin Dutton note the inadequacy of the term “variant” for the Qur’an, given that there is not a singular fixed original, but rather the original itself is “multiformic” to use Dutton’s terminology. See Dutton, “Orality, Literacy and the ‘Seven Aḥruf’ Hadith,” 1–49; also see Muhammad Mustafa Al-Azami,

The History of the Qur’anic Text from Revelation to Compilation (Leicester: UK Islamic Academy, 2003), 154–55. Acknowledging this point, the term is used in the present article to signify a reading that does not conform to the Uthmanic recension. Shady Hekmat Nasser terms such readings “anomalous” and uses the term “irregular” for those readings that are deficient in transmission or grammar, while both are referred to as

shaadh in Arabic. Nasser,

The Transmission of the Variant Readings of the Qurʾān: The Problem of Tawatur and the Emergence of Shawadhdh (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2003), 16.

4 Behnam Sadeghi and Mohsen Goudarzi, “San'a' 1 and the Origins of the Qurʾān,”

Der Islam 87, no. 1–2 (February 2012): 1–129. For this categorization, pp. 3–4.

5 Sadeghi and Goudarzi, 3.

6 Sadeghi and Goudarzi; see also Harald Motzki, “Alternative Accounts of the Qur’an’s Formation,” in

The Cambridge Companion to the Qur’an,

ed. J. McAuliffe, Cambridge Companions to Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 59–76.

7 Nicolai Sinai, “When Did the Consonantal Skeleton of the Quran Reach Closure? Part II,”

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 77, no. 3 (2014): 509–21.

8 See for instance: Sami Ameri,

Hunting for the Word of God (Minneapolis: Thoughts of Light Publishing, 2013); Al-Azami,

History of the Qur’anic Text; Abd al-Fattah Shalabi,

Rasm al-mushaf al-Uthmani wa awham al-mustashriqin fi qira'at al-Qur'an al-Karim (Cairo: Maktabah Wahbah, 1999); Muhammad Mohar Ali,

The Quran and the Orientalists (Norwich: Jamiyat Ihyaa Minhaaj al-Sunnah, 2004). The alternative narrative is discussed below in the section on

qira’ah bil-ma’na.

9 It is anticipated that the present article will form the first in a trilogy with two subsequent articles examining the ʿUthmānic variants and the post-ʿUthmānic readings respectively.

13 Al-A’zami,

History of the Qur’anic Text, 64–65. Al-A’zami lists no fewer than thirty-nine companions by name who memorized the Qur’an directly from the Prophet ﷺ, and this list evidently includes only the most famous who lived to teach others, as the names of those who died in Bi’r Ma’unah and Yamamah have not been preserved.

16 Al-A’zami,

History of the Qur’anic Text, 68.

17 In addition to being recorded in almost all the canonical six works (Bukhārī, Muslim, Abū Dāwūd, Tirmidhī, al-Nasā’ī), the seven

aḥruf narrations are found in numerous early works including the

Jāmiʿ of Maʿmar ibn Rāshid (d. 153 AH),

Muwaṭṭa of Imam Mālik ibn Anas (d. 179 AH), the

Musnad of Abū Dāwūd al-Ṭayālisī (d. 204 AH),

Musnad al-Ḥumaydī (d. 219 AH),

Muṣannaf ibn Abī Shaybah (d. 235 AH), and the

Musnad of Imām Aḥmad (d. 241 AH). Given the voluminous transmitted reports from the earliest era, the fact that the earliest Muslim community understood the Qur’an to be a multiform recitation cannot be logically disputed even by the most skeptical historian.

18 A comprehensive study of the narrations demonstrates that it was reported by no fewer than twenty-three companions through numerous diverse chains. See ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Qāriʾ,

Hadith al-aḥruf al-sabʿ: Dirāsat isnādihi wa matnihi wa ikhtilaf al-ʿulamāʾ fī maʿnāhu wa ṣilatihi bi-al-qirā’āt al-Qurʾānīyah (Beirut: Resalah Publishers, 2002).

19 Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 4991,

kitāb faḍāʾil al-Qurʾān. The hadith of seven

aḥruf are cited in no fewer than four books within

Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhari.

21 Ibn Qutaybah,

Ta’wīl mushkil al-Qurʾān (Cairo: Maktabah Dar al-Turath, 1973), 38–40; see also Abū Shāmah,

al-Murshid al-wajīz ilá ʿulūm tataʿallaq bi-al-kitāb al-ʿazīz (Beirut: DKI, 2003), 90.

23 al-Khaṭṭābī,

Maʿālim al-sunan, (Halab: al-Maṭbaʿah al-ʿIlmiyyah, 1932), 1:293.

24 For further details, see Makkī ibn Abī Ṭālib,

al-Ibānah ʿan maʿānī al-qirāʾāt (Cairo: Dar Nahdah Misr, 1977), 71–79; Abū Shāmah,

al-Murshid al-wajīz, 91-111; al-Zarkashi:

al-Burhān fī ʿulūm al-Qurʾān (Cairo: Dār al-Turāth, 1984), 1:213–27; Ibn al-Jazarī,

al-Nashr, ed. Muḥammad Sālim Muḥaysin (Cairo: Maktabah al-Qahirah, 1978), 1:21–31; ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Qāriʾ,

Hadith al-aḥruf as-sab’ah; Ghanim Qadduri Al-Hamad,

al-Ajwibah al-‘ilmiyyah ‘alá as’ilat multaqá ahl al-tafsīr.

25 Taqi Uthmani,

An Approach to the Qur’anic Sciences (Karachi: Darul Ishaat, 2007), 105–65; Ahmad Ali al-Imam,

Variant Readings of the Qur’an (London: IIIT, 2006); Al-Azami,

History of the Qur’anic Text, 152–64; Abu Ammar Yasir Qadhi,

An Introduction to the Sciences of the Qur’aan (Birmingham: Al-Hidaayah Publications, 1999), 172–202.

26 See Ibn al-Jazarī:

an-Nashr, 1:27; al-Suyūṭī:

al-Itqān, 1:313–14.

27 In our time,

shawādhdh has been used as a designation for all

qirā’āt other than the ten canonical

qirā’āt. The formal classical definition is those readings that lack one of the following three criteria: (1) authentic transmission; (2) conformity to the ʿUthmānic skeletal text; and (3) concordance with conventional Arabic grammar.

28 For a list of these variants see ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Khaṭīb,

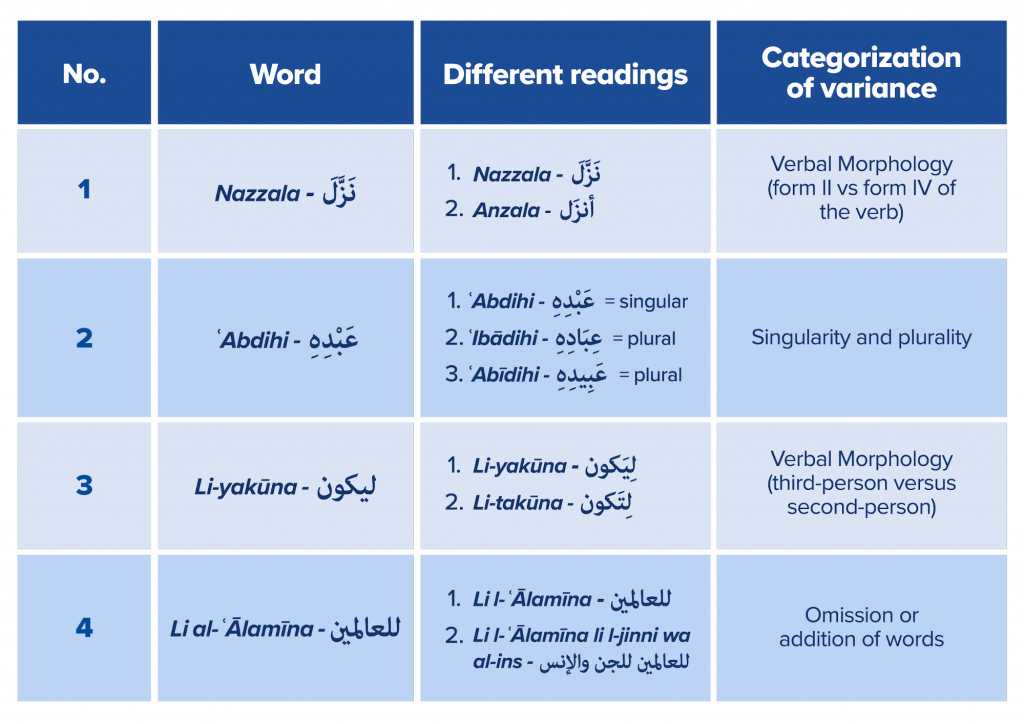

Mu’jam al-qirāʾāt (Damascus: Dār Sa’d al-Din, 2002), 6:315. No. 1 variant 2 is read by Abū Sawwār al-Ghunawī and Abū al-Jawzāʾ, no. 2 variant 2 by ʿĀṣim al-Jaḥdarī and ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr, no. 2 variant 3 by Muʿādh Abū Ḥulaymah and Abū Nahik, no. 3 variant 2 by Ad´ham al-Sadūsī, and no. 4 variant 2 by ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr.

29 Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr,

al-Tamhīd li mā fī al-Muwaṭṭa min al-maʿāni wa-al-asānīd (Rabat: al-Maṭba’ah al-Malakiyyah, 1980), 8:301–2. Shady Hekmat Nasser also adopts a similar approach, pp. 29–30.

32 Ibn Mujāhid,

Kitāb al-sabʿah fī al-qirāʾāt, ed. Shawqi Dayf (Cairo: Dar al-Ma’arif, 1972), 51.

34 For a discussion on this point, see Al-Azami,

History of the Qur’anic Text, 97.

35 ʿAbd Allāh ibn Mas’ud was praised for his recitation by the Prophet ﷺ, being one of the four from whom the Prophet told others to learn the Qur’an (alongside Sālim, Mu’ādh, and Ubayy ibn Ka’b;

Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhari, no. 4999), and being one whose recitation was described “as fresh as how it was revealed” (

Sunan ibn Majah, no. 143,

https://sunnah.com/urn/1251380).

36 Ibn Mujāhid,

Kitab al-sabʿah fī al-qirāʾāt, 67. See also Ghānim Qaddurī al-Ḥamad,

Rasm al-muṣḥaf: Dirāsah lughawīyah tārīkhīyah (Baghdad: al-Lajnah al-Waṭaniyyah, 1982), 623; and Ramon Harvey, “The Legal Epistemology of Qur’anic Variants: The Readings of Ibn Masʿūd in Kufan fiqh and the Ḥanafī madhhab,”

Journal of Qur’anic Studies 19, no. 1 (2017): 72–101, 20, endnote 8.

39 Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhari, no. 4971,

https://sunnah.com/urn/183110;

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 208a,

https://sunnah.com/muslim/1/416. al-Nawawī (d. 671 AH) and al-Qurṭubī (d. 676 AH) both stated that this was a revealed verse that was abrogated. See al-Nawawī,

al-Minhāj sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim bin Ḥajjāj (Cairo: Mu’assasat Qurtubah, 1994), 3:102; al-Qurṭubī,

al-Jāmiʿ li-aḥkām al-Qur’

ān, ed. ʿAbd Allāh al-Turkī (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Risalah, 2006), 16:83. Al-Kirmānī (d. 796 AH) adds the possibility of it being

tafsīr:

Sharḥ al-Kirmānī ala Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī (Beirut: DKI, 1971), 9:211.

40 Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd ul-Raḥmān al-Ṭāsān,

al-Masāḥif al-manṣuba lil-ṣaḥābah wa-al-radd ʿalā shubuhat al-muthārah (Riyadh: Dar al-Tadmuriyyah, 2016).

41 Variant readings that differ from the ʿUthmānic codex must be studied by hadith standards because, unlike the

qirā’āt, they have not been transmitted by the ritual practice of one generation of Muslims from the next, but rather only as isolated reports. The successively transmitted uninterrupted living oral tradition has always been the primary factor in establishing the validity of one’s recitation.

42 While the 540 reported variants likely overestimates the quantity, the 20 variants with an authentic chain of transmission likely underestimates it due to the fact that some of the other variants are demonstrated in manuscripts.

43 In their 2012 essay studying folios of the lower text, Benham Sadeghi and Mohsen Goudarzi write: “The lower writing of Ṣan‘ā’ 1 clearly falls outside the standard [Uthmanic] text type. It belongs to a different text type, which we call C-1. . . . Ṣan‘ā’ 1 constitutes direct documentary evidence for the reality of the non-‘Uthmānic text types that are usually referred to as ‘Companion codices.’ . . . C-1 confirms the reliability of much of what has been reported about the other Companion codices not only because it shares some variants with them, but also because its variants are of the same kinds as those reported for those codices” (Sadeghi and Goudarzi, 17–20). They also note that since the Uthmanic

mushaf always agrees with either C-1 or Ibn Masʿūd’s text (i.e., it is always in the majority) in the case of difference, this suggests either that it was compiled from a critical examination of other textual sources or that it is the most faithful reproduction of the Prophetic prototype (21–22). Both of these scenarios are entirely consistent with what the Muslim tradition states.

44 His father is, of course, none other than the famous Abū Dāwūd al-Sijistānī (d. 275 AH) who compiled the

Sunan.

45 Ibn Abī Dāwūd,

Kitāb al-maṣāḥif, ed. Muhib al-Din Wa’iz (Beirut: Dar al-Basha’ir al-Islamiyyah, 2002), 2:284.

46 al-Ṭāsān,

al-Maṣāḥif al-manṣuba lil-ṣaḥābah, 63–64.

48 Ibn al-Nadīm,

Kitib al-fihrist, ed. Rida Tajadud (Teheran: 1971), 29.

49 Al-Azami,

History of the Qur’anic Text, 215.

51 al-Qurṭubī,

al-Jāmiʿ li-aḥkām al-Qur’

ān, ed. ʿAbd Allah al-Turkī (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Risalah, 2006), 177.

52 al-Qurṭubī. Amongst Muslim scholars, there are broadly three views with respect to addressing these narrations that Ibn Masʿūd did not include these chapters in his

mushaf. The first group of scholars, including Ibn Ḥazm, al-Nawawī, Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī, and others, rejected these narrations entirely. The second group of scholars accepted the validity of these narrations while interpreting them in a different light, for instance suggesting Ibn Masʿūd had not personally heard the Prophet recite them in

salah, as Sufyān ibn Uyaynah said. The third group of scholars stated that he left them out due to their widely known status, as mentioned by al-Bāqillānī, al-Zarkashī, al-Bayḥaqī, and Abu’l-Faḍl al-Rāzī, in addition to the others cited in this article. For a discussion of the subject, see al-Tāsān,

al-Masāhif, 390–97.

53 Cited in al-Nawawī,

al-Minhāj sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim ibn Ḥajjāj, (Cairo: Mu’assasat Qurtubah, 1994), 6:157–58.

54 Muḥammad ʿAbd al-ʿAẓīm al-Zarqānī,

Manāhil al-ʿirfan fī ʿulūm al-Qurʾān (Beirut: DKI, 2013), 1:200. See also the discussion of Theodor Nöldeke who argues on the basis of stylistic features that this invocation clearly does not match the Qur’anic style; Theodor Nöldeke, Friedrich Schwally, Gotthelf Bergsträsser, Otto Pretzl, and Wolfgang Behn,

The History of the Qur’an (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 241–42.

55 Ibn Ḥazm,

al-Muḥallá (Beirut: DKI, 2003), 1:32. See also al-Zarkashī,

al-Burhān fī ʿulum al-Qurʾān, 2:128; and Al-Azamī,

History of the Qur’anic Text, 201.

57 Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 1452a,

https://sunnah.com/muslim/17/30. This narration refers to the extent of infant breastfeeding that is sufficient to establish a familial relationship under Islamic rulings.

61 For a detailed review, see Nāsir ibn Saʿūd al-Qithamī, “al-ʿArḍah al-akhīrah: Dalālatuha wa atharuhā,”

Majallah Maʿhad al-Imām al-Shaṭibī li-Dirasah al-Qurʾāniyyah, 2013, no. 15.

63 Sunan Sa’īd ibn Mansūr (Riyadh: Dar al-Samee’, 1993), 1:239.

64 Ibn al-Jazarī,

al-Nashr, 1:8.

65 Osama Alhaiany, “al-ʿArḍah al-akhīrah lil-Qurʾān al-Karīm wa-al-aḥadīth al-wāridah fīhā jamʿan wa dirāsah,”

al-Majallah al-Ulum al-Islamiyyah, no. 10, p. 67.

66 al-Baghawī,

Sharḥ al-sunnah (Beirut: Al-Maktab Al-Islami, 1983), 4:525–26. Witnessing the final review would attest to Zaid’s merit in leading the committee commissioned by Uthman. However, Ibn ʿAbbās has a statement reported from him that states that ʿAbd Allāh ibn Mas’ud attended

al-ʿarḍah al-akhīrah (

Musnad Aḥmad 3422). If both ʿAbd Allāh ibn Mas’ud and Zayd attended, then it doesn’t make sense why Ibn Masʿūd would have variant readings from that which was established by Zayd in the ʿUthmānic codex. And if ʿAbdullah attended and Zaid did not, then why would the

sahabah unanimously adopt a codex that did not match

al-ʿarḍah al-akhīrah? Abū Jaʿfar al-Naḥḥās answers that since the reading of ʿAsim comes from ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʿūd, we know that Ibn Masʿūd did not only teach and recite in one

ḥarf, rather he also had the same

ḥarf as Zayd in addition to one that differed. See al-Naḥḥās,

al-Nāsikh wa-al-mansūkh (Riyadh: Dar al-Asimah, 2009), 2:408. On ʿAsim’s transmission, see al-Ṭaḥāwī,

Tuḥfat al-akhyār bi-tartīb mushkil al-āthār, ed. Khalid Mahmud al-Rabat (Riyadh: Dar al-Balansiyya, 1999), 8:435.

67 al-Naḥḥās,

al-Nāsikh wa-al-mansūkh, 2:407.

68 Ibn Taymīyah,

al-Fatāwá al-kubrā (Beirut: DKI, 1987), 4:418.

70 Note that Abū Bakr al-Bāqillānī and a few other scholars differed with this position and believed that all the seven

aḥruf are contained within the ʿUthmānic codices. However, the majority believed that at least some of the

aḥruf were left out.

71 Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī,

Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī, ed. al-Turkī (Cairo: Dār Hajar, 2001), 1:59–60.

72 al-Naḥḥās,

al-Nāsikh wa-al-mansūkh, 2:405.

Fa-arāda ʿUthmān an yakhtār min al-sabʿah ḥarfan wāḥid wa huwa afṣaḥuhā.

73 Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr,

al-Istidhkār (Damascus: Dar Qutaibah, 1993), 8:45.

74 ʿAlī ibn Ismaʿīl al-Abyārī,

al-Taḥqīq wa-al-bayān fī sharḥ al-burhān fī uṣūl al-fiqh (Doha: Wizārat al-Awqāf wa al-Shuʾūn al-Islāmīyah Qatar, 2013), 2:792.

75 Ibn al-Qayyim,

al-Ṭuruq al-ḥukmīyah fī al-siyāsah al-sharʿīyah, (Mecca: Dār ʿĀlam al-Fawāʾid, 1428 AH), 1:47–48; Ibn al-Qayyim,

Iʿlām al-muwaqqiʿīn (Dammam: Dār ibn al-Jawzī, 2002), 5:65.

76 See also Mannāʿ al-Qaṭṭān,

Mabāḥith fī ʿulūm al-Qur’ān (Cairo: Maktabah Wahbah, 1995), 158.

77 Makkī states, "There ceased to be implementation of that which differed from the script of the (ʿUthmānic )

muṣḥaf from the seven

ahruf in which the Quran was revealed, based upon the unanimous consensus on the script of the

muṣḥaf. Thus, the

muṣḥaf was written based on one

ḥarf, and its script accommodates more than one

ḥarf as it was void of dotting and vowels." See Makkī ibn Abī Ṭālib,

al-Ibānah ʿan maʿānī al-qirāʾāt (Cairo: Dār Nahdah Misr, 1977), 34. This quote is of interest because it demonstrates that while opinions on this subject are conventionally divided into three groups—those who say all

aḥruf are preserved (e.g., al-Bāqillānī), those who say only one is preserved (e.g., al-Ṭabarī), and those who say the ʿUthmānic

muṣḥaf was deliberately written (free of vocalization and diacritics) to accommodate more than one

ḥarf (Ibn al-Jazarī)—Makkī fell into a fourth category, suggesting that although the

muṣḥaf was deliberately written according to one

ḥarf, the script still accommodated other readings. See also Makkī ibn Abī Ṭālib,

al-Hidāyah ilā bulūgh al-nihāyah (Sharjah: University of Sharjah, 2008), 4:2911–12.

78 Ibn al-Jazarī,

al-Nashr, 1:31. He writes, “As for whether ʿUthmānic codices encompass all the seven

aḥruf then this is a major topic . . . the position taken by the majority of the scholars from the earlier and later generations and the Imams of the Muslims is that these codices encompass that which the text can accommodate from the seven

aḥruf.”

79 Ibn Ḥajar,

Fatḥ al-Bārī (Riyadh: Dār al-Ṭaybah, 2005), 11:195–96. He further explains that this was a reason for the textual variants between ʿUthmānic codices, to increase the number of readings that could be accommodated.

80 Abū al-ʿAbbās ibn ʿAmmār al-Mahdawī,

Sharḥ al-hidāyah (Riyadh: Maktabah Rushd, 1995), 5.

81 As demonstrated by the view of Makkī ibn Abī Ṭālib, there is no conflict between the view that the committee of ʿUthmān compiled the Qur’an according to one

ḥarf and the view that some of the other

aḥruf remained because even if the committee may have primarily had one of the various readings in mind when they transcribed the codex, that does not change the fact that other readings could still be accommodated by the skeletal text. See also Ghānim Qaddurī al-Ḥamad,

Rasm al-muṣḥaf: Dirāsah lughawīyah tārīkhīyah, 152.

82 Makkī ibn Abī Ṭālib,

al-Ibānah ʿan maʿanī al-qirāʾāt (Cairo: Dar Nahdah Misr, 1977), 42.

83 Abū Bakr al-Bāqillānī,

al-Intiṣār lil-Qur’ān (Beirut: Dar Ibn Hazm, 2001), 1:153. He mentions as an example the reading “

salāt al-ʿaṣr” in 2:238.

84 Abū Ḥayyān,

al-Baḥr al-muḥīṭ (Beirut: Dār al-Fikr, 2010), 1:260.

86 al-Nawawī,

al-Minhāj sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim bin al-Ḥajjāj (Cairo: Mu’assasat Qurtubah, 1994), 6:157.

87 Ibn al-Jazarī,

al-Nashr fī al-qirā’āt al-ʿashar, 1:44.

88 Related in al-Qurṭubī,

al-Jāmiʿ li-aḥkām al-Qur’

ān, ed. ʿAbd Allāh al-Turkī (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Risalah, 2006), 1:134. See also, Ghānim Qaddūrī al-Ḥamad,

Muḥāḍarāt fī ulūm al-Qurʾān (Amman: Dar Ammar, 2003), 145.

89 al-Naḥḥās,

I’rab al-Qurʾān, (Riyadh: Dār ʿĀlam al-Kutub, 1988), 1:321–2. Note however the previously mentioned narration concerning this being an abrogated reading:

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 630,

https://sunnah.com/muslim/5/264.

90 Reported in

Sunan Sa’īd ibn Mansūr (d. 227 AH) according to al-Suyūṭī,

al-Itqān fī ʿulūm al-Qurʾān (Beirut: DKI, 2000), 1:119.

91 Abdul Jalil, “Dhahirat al-ibdāl fī qirāʾat ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʿūd wa-qīmatuhā al-tafsīrīyah,”

Journal of Qur’anic Studies 15, no. 1 (2013): 168–213, 210.

93 al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī,

al-Mustadrak ʿalá al-ṣaḥiḥayn, ed. Yūsuf ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Marʿashī (Beirut: Dār al-Maʿrifah, 1986), 2:451; al-Qurṭubī,

al-Jāmiʿ li-aḥkām al-Qur’

ān, ed. ʿAbd Allāh al-Turkī (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Risalah, 2006), 19:132. The viewpoint adopted by al-Zarqānī is that Ibn Masʿūd selected another revealed

ḥarf that was easier for the man to recite. al-Zarqānī,

Manāhil al-ʿirfān, 1:133.

94 Taqi Uthmani,

An Approach to the Qur’anic Sciences (Karachi: Darul Ishaat, 2007), 249–51.

95 The theories of

qirā’ah bi-al-talaqqī and

qirā’ah bi-al-ma’ná are explanations of how new readings emerged, while the concepts of abandoned

ḥarf and abrogated

ḥarf are explanations for how readings ceased to exist. On the supposition of

qira’ah bil-ma’ná, the abandoned

ḥarf explanation would naturally be adopted.

96 Dutton, “Orality,” 32–34.

97 Reported by al-Dhahabī in

Siyar aʿlām al-nubalāʾ, 1:347. Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī was known to have permitted transmission of hadith based on meaning (

riwayah bi-al-maʿná); however, he also commented on the famous seven

aḥruf hadith by saying, “It has reached me that these seven

aḥruf are basically one in meaning, they do not differ about what is permissible or prohibited” (

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 819a,

https://sunnah.com/muslim/6/330). Taken together with his previous statement, it may be that he considered the seven

aḥruf tradition to essentially be the Prophet’s way of describing

qirā’ah bi-al-ma’ná. The other possibility is that he was simply referring to the fact that revealed

aḥruf use

taqdīm wa-al-ta’khīr in Divine speech so there is no reason why human speech cannot.

98 Ṭaḥāwī,

Sharḥ mushkil al-āthār, ed. Shu'ayb al-Arna'ūṭ, 16 vols. (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Risalah, 1994), 8:118.

99 “And it is possible that in the beginning of Islam it was legislated for people to exchange one

ḥarf for another for instance instead of ʿ

alīm qadīr using

ghafūr raḥīm, and then it was abrogated after that.” al-Baqillani,

al-Intiṣār, 1:370.

100 After quoting the incident of Abū al-Dardāʾ teaching a man to recite

ṭa’ām al-fājir, al-Zamakhsharī writes, “And this is used to prove the permissibility of exchanging one word for another so long as it gives the same meaning.” He goes on to use this as an explanation for Abū Ḥanīfah permitting recitation in Persian. al-Zamakhsharī,

al-Kashshāf (Beirut: Dar al-Marefah, 2009), 1003.

101 Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī,

The Epistle on Legal Theory: A Translation of Al-Shafii's Risalah, trans. Joseph Lowry (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 119.

103 Abu Shāmah,

al-Murshid al-wajeez ila ulum tata’alaq bil-Kitab al-Aziz (Beirut: Dar al-Kotob al-Ilmiyah, 2003), 105. See also p. 85 where Abu Shāmah states the ʿUthmānic recension was based only on the revealed wording (

lafdh al-munazzal) and not the substituted synonym words (

lafdh al-murādif).

104 Abu Shāmah, 109. The quote from al-Baghawī reads, “The meaning of these

aḥruf is not that every group reads according to what matches their dialect without instruction (

min ghayrī tawqīf) but rather all of these

ḥurūf are mentioned (

mansusah) and all of them are the speech of God (

kalām Allah) with which the trustworthy spirit (i.e., Jibrīl) descended upon the Prophet.” See al-Baghawī,

Sharḥ al-sunnah (Beirut: Maktabah Islami, 1983), 4:509.

105 Ibn Hajar,

Fatḥ al-Bārī (Riyadh: Dar al-Taybah, 2005), 11:191. Commenting on Ibn Hajar’s quote, ʿAbd al-Hādī Hamītu supports this view and states this concession was present until the unanimous consensus of the companions on the ʿUthmānic codex. Ḥamītu,

Ikhtilāf al-qirāʾāt wa atharuhu fī al-tafsīr wa istinbāṭ al-aḥkām (Manama: Islamic Affairs Ministry, 2010), 40.

106 In addition to the above questions, there are other matters of uncertainty in the theory of

qirā’ah bi-al-maʿná. Did the Prophet ﷺ himself recite according to meaning? Was the primary impetus for reciting according to meaning the fact that a companion had an imperfect recollection of how the verse was recited by the Prophet and, thus, if they had recourse to a written parchment, would they subsequently revert back to the Prophet’s reading?

107 Arabic translation of Ignaz Goldziher’s work by 'Abdul-Halim Najjar,

Madhahib al-tafsīr al-Islāmī (Cairo, 1955). In his doctoral dissertation, Shady Hekmat Nasser claims that Ibn ʿAṭīyah “openly embraces” this view that the canonical readings are not of Divine or Prophetic origin but rather “the result of the Readers’ interpretation (

ijtihād) of the defective Uthmanic consonantal script” (7). However, in the provided reference, Ibn Aṭiyyah actually says nothing of the sort. What Ibn Aṭiyyah actually says is that the seven canonical readers used their

ijtihād to select whatever variation from the

aḥruf they found would conform to the

mushaf, not that the variation itself was invented by

ijtihād.

Ijtihād was thus in selection, not invention. See Ibn ʿAṭīyah,

al-Muḥarrar al-wajīz (Beirut: DKI, 2001), 1:48.

108 See, for instance, al-Azami,

History of the Qur’anic Text, 155–59.

110 al-Naysābūrī,

al-Mustadrak ʿalá al-ṣaḥīḥayn,

2:451.

111 Musnad Abī Yaʿla, no. 4022. Ibn Jinnī (d. 392 AH) discusses this and many other examples. While discussing the variant reading ascribed to Anas ibn Mālik for 9:57 and Anas’s statement that

yajmahūn, yajmazūn, and

yashtadūn mean the same thing, Ibn Jinnī states, “And the apparent meaning of this is that the

salaf would recite one letter in place of another without a precedent simply on the basis of agreement in meaning... However, giving the benefit of the doubt to Anas would entail believing that a reading had already preceded with these three words—

yajmahūn, yajmazūn, yasthadūn—so it was said ‘Recite with any that you wish.’ So all of them constitute a reading heard from the Prophet due to his saying, ‘The Qur’an has been revealed on seven

aḥruf, all of them healing and sufficient.’” See Ibn Jinnī,

al-Muḥtasib fī tabyīn wujūh shawadhdh al-qirāʾāt wa al-īḍāḥ ʿanhā (Dar Sazkin, 1406)

, 1:296.

112 For a comprehensive discussion of these reports, refer to Hamzah Awad, “Sharṭ Muwāfaqat al-Rasm al-ʿUthmānī” (PhD diss., University of Batna, Algeria, 2014), 124–38. If authentic, these reports are simply understood to relate to them expressing a preference for the reading they learned directly from the Prophet ﷺ over a reading they were unfamiliar with.

113 Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 4695,

https://sunnah.com/urn/180290. Ibn Ḥajar explains that she was likely unfamiliar with the interpretation of the other reading. Ibn Ḥajar,

Fatḥ al-Bārī (Cairo: Dār al-Rayan lil-Turath, 1986), 218,

https://library.islamweb.net/newlibrary/display_book.php?idfrom=8477&idto=8478&bk_no=52&ID=2464.

114 Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī,

Tafsīr, 23:309–10. Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr (d. 463 AH) comments that Ali considered the ʿUthmānic reading to be a valid revealed reading but was expressing a preference for the reading he had learned. Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr,

al-Tamhīd (Egypt, 1967), 8:297; see also Hamzah Awad, “Sharṭ Muwāfaqah al-Rasm al-ʿUthmānī,” 138.

115 In verse 17:5, it is stated that Abū al-Sammal al-Adawi recited “

faḥāsu” with a ح instead of a ج and when asked about it stated that they meant the same thing. Ibn Jinnī (d. 392 AH) states, “And this indicates that some of the reciters would choose readings without precedent (

yatakhayyar bi-la riwāyah)” (Ibn Jinnī,

al-Muḥtasib, 2:15). However, Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d. 606 AH) states about this variant, “It is necessary to understand that as him mentioning it as

tafsīr of the words of the Qur’an, not that he actually made it part of the Qur’an, since if we were to adopt what Ibn Jinnī says it would entail no longer relying on the wording of the Qur’an and it would permit each individual to express a meaning using a word they thought was concordant with that meaning and then either being correct in that belief or erring, and this is an attack on the Qur’an, so it is evident that we must understand it according to what we have mentioned.” See al-Rāzī,

Tafsīr al-Fakhr al-Rāzī (Cairo: Dār al-Fikr, 1981), 30:177.

116 Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Ḥibbān, no. 747.

117 Ibn Mujāhid,

Kitāb al-sabʿah fī al-qirāʾāt, 51. Similar statements have been related from Zaid ibn Thabit (al-Bayhaqi,

al-Sunan al-kubrá, no. 3900) and Urwah ibn al-Zubayr.

118 al-Nasāʾī,

al-Sunan al-kubrá, 2:539.

119 The essence of the story is in

Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhari, no.

3617,

https://sunnah.com/bukhari/61/124; however, the details of the man substituting words are found in

Musnad Aḥmad (no. 13312),

Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Ḥibbān (no. 751), and

Musnad Abī Dāwūd al-Ṭayālisī (no. 2119), among other sources.

120 al-Qurṭubī,

al-Jāmiʿ li-aḥkām al-Qurʾ

ān, ed. ʿAbd Allāh al-Turkī (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Risalah, 2006), 12:180–81. al-Bayḥaqī,

Dalā’il al-nubuwwah (Beirut: DKI, 1988), 7:160.

121 Sa’d said, “Verily the Qur’an was not revealed to ibn al-Musayyib nor his family.”

al-Nasa’i,

al-Sunan al-kubrá, no. 10996;

Sunan Saʿīd ibn Manṣūr, 1:597.

122 al-Ṭaḥāwī,

Mushkil al-āthār, 8:132–33.

123 Mustadrak al-Ḥākim, no. 5381. In another narration, we find that ʿUmar considered some of Ubayy’s variant readings to have been abrogated. ʿUmar said, “Ubayy is the best of us in recitation yet we leave some of what he recites. Ubayy says, ‘I have taken it from the mouth of Allah’s messenger so I will not leave it for anything.’ However, Allah says {We do not abrogate or cause a revelation to be forgotten except that we bring that which is better than it.}” (

Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 5005,

https://sunnah.com/bukhari/66/27). As Ibn Ḥajar explains, “ʿUmar is implying that Ubayy may not have been aware of a reading’s abrogation.”

Fatḥ al-Bārī (Riyadh, 2001), 8:17.

124 al-Naysābūrī,

al-Mustadrak ʿalá al-ṣaḥīḥayn, 2:451. This is analogous to the Prophet ﷺ permitting one who cannot recite any Qur’an to simply repeat

subḥān Allāh (glory be to God) or

alḥamdu lillāh (praise be to God) instead. See

Sunan Abī Dāwūd, no. 832,

https://sunnah.com/abudawud/2/442.

125 See Ibn al-Salāḥ,

Fatāwá wa masāʾil Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ (Beirut: Dar al-Ma’rifah, 1986), 1:233; Ibn Taymīyah,

Majmūʿ al-fatāwá (Mansoura: Dar El-Wafaa, 2005), 13:214; Ibn al-Jazarī,

al-Nashr fī al-qirā’āt al-ʿashar, 1:32; al-Suyūṭī,

al-Itqān (Beirut: Dar al-Kitab al-Arabi, 1999), 1:263; al-Zarkashī,

al-Burhān fī ulūm al-Qur’ān, 1:332–33, who cites Ibn al-Ḥājib.

126 al-Qurṭubī,

al-Jāmiʿ li-aḥkām al-Qurʾ

ān, ed. ʿAbd Allāh al-Turkī (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Risalah, 2006), 21:329–30. He also points out that the narration from Anas being used as proof is in fact a weak narration due to a disconnection in the chain.

127 Adrian Brockett writes, “Thus, if the Qur’an had been transmitted only orally for the first century, sizeable variations between texts such as are seen in the hadith and pre-Islamic poetry would be found and if it had been transmitted only in writing, sizeable variations such as in the different transmissions of the original document of the Constitution of Medina would be found. But neither is the case with the Qur’an.” Adrian Brockett, “The Value of the Hafs and Warsh Traditions for the Textual History of the Qur’an,” in

Approaches to the History of Interpretation of the Qur’an, ed. Andrew Rippin (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), 44.

128 See Ibn Taymīyah,

Jāmiʿ al-masāʾil (Jeddah: Majma’ al-Fiqhī al-Islāmī, 1422), 1:133.

129 Discussed under the section “Critiquing a different paradigm:

qirāʾah bi-l-maʿná.”

Taken from https://yaqeeninstitute.org/ammar-khatib/the-origins-of-the-variant-readings-of-the-quran