Codex Topkapı Sarayı Medina 1a - A Qurʾān Located At Topkapı Sarayı Museum, Istanbul, From 1st/ 2nd Century Hijra

Reference

|

: Sahih

Muslim Introduction 26

|

In-book

reference

|

: Introduction,

Narration 25

|

Understanding the Sana’a manuscript find.

بسم الله Perhaps the most intriguing discovery in the field of Qur’anic studies in the last several decades is the Sana’a manuscript finding. This is because they represent a Qur’an that is uniquely non-Uthmanic, that is, one of the manuscripts that does not descend from the text that the third Caliph Uthman (ر) had compiled. In other words, this valuable find is currently the only manuscript we have that survived the destruction of the non-Uthmanic variants by the 3rd caliph and his committee. Before we look at an analysis of the manuscripts, it’s important to understand *what* the Qur’an actually is and is not with regards to its text.

The Qur’an during the time of the Prophet Muhammad (ص)

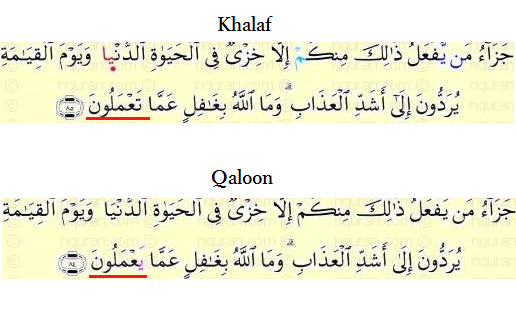

Islamic tradition records that during the time of the Prophet, there was an authoritative allowance for variance in the possible readings of the Qur’an in order to facilitate easier recital and memorization by the arabs[1][2].This is because the arab tribes did not all speak the same dialect as the Qurayshi arabs, the tribe of the Prophet himself. The variation between the dialects at most encompass the replacing words for their synonyms. I have previously given an example of a Quranic variant in another article of mine, for the sake of demonstration here is that same example: This point cannot be stressed enough: The Qur’an was allowed to have certain selected variants in them by the permission of the author. Nobody was allowed to simply replace any word they liked because it was difficult to pronounce or they did not like it: The change in wording had to be approved by the Prophet himself.

This point cannot be stressed enough: The Qur’an was allowed to have certain selected variants in them by the permission of the author. Nobody was allowed to simply replace any word they liked because it was difficult to pronounce or they did not like it: The change in wording had to be approved by the Prophet himself.

The significance of the multiple readings.

It has also been held by Muslims that any one reading of the Qur’an is sufficient to know the contents of the whole Qur’an. This is because the allowance of multiple readings is a concession, not a requirement for knowing the whole Qur’an itself [3].

The Uthmanic text and the current variant readings.

When Uthman compiled the Qur’an, what he essentially did was to limit the number of the possible readings of the Qur’an. He was unable (or perhaps unwilling) to confine the Qur’an to just one qira’at (reading) because the arabic text at the time did not have dots. There were multiple ways to read the mushaf (written Qur’anic text) because of this. As such, some of the dialects survived: As long as any dialect fit the Uthmanic manuscripts, and actually did trace back to the Prophet himself, it was and still is considered a divinely inspired and authoritative reading. Take the example I have given above: The word underlined can be read “Ta’maloona” and “Ya’maloona”, while both of them have the same skeletal (ie. not dotted) text, they still sound and mean a different thing.

EDIT 10th April 2015: A minor correction, the arabic script DID have dots. Scribes used them to their own discretion. However it seems that with some words of the manuscript the dots were omitted, possibly to allow for multiple readings.

Now that this is out of the way, let’s discuss the important things: The Sana’a manuscripts!

The Sana’a Manuscripts

In 1972 an assorted collection of old parchment pieces were found hidden between the ceiling of the Grand Mosque of San’a’ and the roof, of these are several Qur’anic manuscripts. Very intriguingly, one group of such Qur’anic manuscripts contain two Qur’ans: The original text which was erased and written over with another Qur’anic text. Scholars can read both the erased and the apparent text (called the “lower” and the “upper” text respectively) due to modern lighting methods.

In this article we shall look at both the upper and lower texts individually.

The upper text

The upper text has been found to be the standard Uthmanic Qur’an we have today[4]. The main differences between the Uthmanic Qur’an and the upper Sana’a’ text are mostly due to how words are spelled[5].

Of more interest is the dating of the text itself. The upper text exhibits the type of writing style that you would typically see in the first century: some time between the death of the Prophet (632AD) to the start of the 7th century (700AD) is quite feasible. Sadeghi states that there isn’t enough information on early writing styles to narrow the dating further[6] but a guess could be taken. Since the lower text is non-Uthmanic, and the upper text is Uthmanic, and because the upper text was written over the lower one, what possibly could have taken place is that scribes were simply seeking to replace the lower text with the upper one as soon as they received the Uthmanic version with the order to adopt it. This means that the upper text could date from around ~650AD, two decades from the death of the Prophet (or when the Uthmanic compilation took place). However this is all just guesswork: all we know for certain is that it is from the first century of Islam.

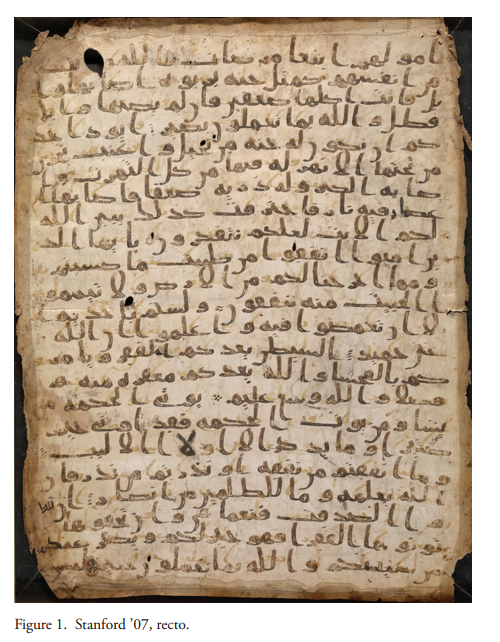

Before we move on to the lower writing here’s a picture of the manuscript (upper text visible) as it is: I am not sure whether the faded writing is the lower text that has become apparent or simply the writing on the other side of the page showing through. It is probably the former:

I am not sure whether the faded writing is the lower text that has become apparent or simply the writing on the other side of the page showing through. It is probably the former:

In Ṣan‘ā’ 1, as with some other palimpsests, over time the residue of the ink of the erased writing underwent chemical reactions, causing a color change and hence the re-emergence of the lower writing in a pale brown or pale gray color. Sana’a’ 1 (page 6)

The lower text

The lower text of the sana’a’ manuscripts are of enormous interest because they are considered to non-Uthmanic. Historical reports tell us that as the Qur’an was promulgated by the Prophet Muhammad (ص), there arose differences in the text of the Qur’an in terms of dialectal variation (refer to start of article). As Islam started to spread to further lands, new converts started to dispute over which of the dialects of the Qur’an was “better” or “proper”[7], Uthman (ر) made the decision to resort to one text that would put an end to the disagreements. He went about doing this by taking the existent manuscripts and recitations (from people’s memories) and writing down the most popular reading for each of the verses, as long as the manuscript or the person’s memory had taking directly from the Prophet (ص) himself. The source manuscripts were then burned and the new, Uthmanic Qur’an was sent to the regional centres of the Islamic world.

I recall this familiar account so that we have a clear understand of what the variants present in the lower text of the San’a’ manuscripts actually are.

Dating the lower text

Just like the upper text, the lower text is written in a very early writing style. Unlike the upper text, however, it is possible to use radio carbon dating to find an approximate age for the it. As we know, there was very little literary activity in the Arabian peninsula before the Qur’an. Simply put, there was nothing else to write. This manuscript is made of vellum, which requires the use of animal skin: its size is also large enough to indicate that a whole flock of animals was needed to create this copy of the Qur’an[9]. Since writing had only just started gaining importance in the Hijaz during the early years of Islam, it is very unlikely that people simply had a whole stack of vellum simply lying around: it would have had to be created and then written on shortly afterwards.

Knowing this, it is possible to find the date of the lower text (the first thing written on the parchment) by carbon-dating the parchment itself, since they would be similar. The results are quite exciting.

Results of radio-carbon dating Sana’a’ parchment[10]

To highlight the significance of the results, I have created a table with the age of the parchment relative to the traditional death date of the Prophet (ص):

What is significant about the dating is that there is a very good chance that this was written while the companions were still alive. This is very important in learning about the text of the Qur’an in its very early stages.

The Text of the Lower Sana’a’ Manuscripts and its non-Uthmanic nature

The type of Qur’an the lower writing represents is non-Uthmanic. This is obvious because it has a lot of variants not found in the Uthmanic version. If the person writing down this Qur’an was copying from the Uthmanic version, then we would expect it to be very similar to the Uthmanic version. It is not. Though the variants are quite minor, there are a lot of them, and there are some major variants such as those found in the following table which cannot be explained by scribal error alone.

Sadeghi, Goudarzi and Bergmann have named the Sana’a’ manuscript as a “Companion Codex”. Islamic literary sources, as we have already seen, tell us that the Qur’an was revealed in different dialects, and sometimes the Prophet taught one companion a surah differently to another (with differences in wording). It was only after Uthman standardized one codex did the other ‘companion codices’ fall out of use. The variants in this manuscript are the same types of variants the Islamic sources tell us. Here are the biggest variants:

PRIVACY

The differences between this codex and the Uthmanic one can be summarized as follows[11]:

1. Variants which arose due to the Prophet teaching the Qur’an differently. The variants in this category are as equally authoritative as Uthmanic readings.

2. Scribal errors such as accidental word omission, assimilation of parallels, et cetera.

As the text is non-Uthmanic, and is very old, it probably represents some sort of companion reading of the Qur’an that is different from the Uthmanic one. In a sense, this is probably the type of manuscript that Uthman would have taken to write his codex and then would have had burned.

On a final note, I hope I have made clear that the fact that this Qur’an differs from the Uthmanic one does not mean that the Qur’an is somehow “changed”. If I were to do a google search for “Sana’a’ manuscripts” I am taken to a list of Christian apologetics websites that misrepresent the Muslim understanding of the Qur’an. We already have the original, as the Uthmanic copy along with its readings is ensured to be a perfect representation of the ‘Prophetic prototype’, this manuscript is simply an extra version that represents some other reading. As long as one of the divinely authorized readings reach us, we have the whole Qur’an [12][13]. On the other hand, this new discovery is an enormous find since it goes a very long way to strengthening the Muslim position.

What the Sana’a’ manuscripts can tell us about the Qur’an.

1. Uthman did not change the Qur’an.

This contention is quite a common one, even though it could be dispelled by simply reading any historical account of the Uthmanic compilation, it has been repeated very often among apologetics circles, even through the mouths of scholars[14].

If historical reports from the Islamic sources constitute good evidence to prove otherwise, that Uthman did not change anything from the Qur’an, this manuscript is even stronger evidence for this, since it is flesh-and-blood proof. There is nothing in the manuscript so far that suggests any meaningful difference from the standard Qur’an. There is no proof that Uthman somehow added any theological or legal idea into the Qur’an. The biggest differences are words being used in place of their synonyms. This manuscript, for the first time ever, gives us hard physical evidence for something Muslims have already known: Uthman was sincere in his efforts to compile the Qur’an.

2. The Qur’an really did exist during the time Muslims say it did.

This will probably come as a surprise to some of you: some revisionist scholars have held that the Qur’an is some sort of composite text originating later than the traditional dating. The easiest way to disprove that something does not exist is to show that object existing! Since we actually do have a Qur’an dating from during this time, we can safely put to rest any fanciful ideas on the origins of the Qur’an.

The manuscript also confirms a part of the Islamic Hadith tradition. Though these sources are written much later they are remarkably accurate in telling us that there were early manuscripts owned by the companions of the Prophet that had variants. They also relate to us what types of variants are found in these manuscripts, and at times the variants mentioned in the Islamic literature is word for word the same as those that are found in this particular manuscript. Sadeghi and Bergmann conclude on this point that:

It is now equally clear that recent works in the genre of historical fiction are of no help. By “historical fiction” I am referring to the work of authors who, contentedly ensconced next to the mountain of material in the premodern Muslim primary and secondary literature bearing on Islamic origins, say that there are no heights to scale, nothing to learn from the literature, and who speak of the paucity of evidence. Liberated from the requirement to analyze the literature critically, they can dream up imaginative historical narratives rooted in meager cherry-picked or irrelevant

evidence, or in some cases no evidence at all. They write off the mountain as the illusory product of religious dogma or of empire-wide conspiracies or mass amnesia or deception, not realizing that literary sources need not always be taken at face value to prove a point; or they simply pass over the mass of the evidence in silence.A pioneering early example of such historical fiction was Hagarism, written by Patricia Crone and Michael Cook. While few specialists have accepted its narrative, the book has nevertheless profoundly shaped the outlook of scholars. It has given rise to a class of students and educators who will tell you not only that we do not know anything about Islamic

origins, but also that we cannot learn anything about it from the literary sources.All this would be good and well if the mountain of evidence had been studied critically before being dismissed as a mole hill; but the modern critical reevaluation of the literary evidence has barely begun. And, significantly, any number of results have already demonstrated that if only one takes the trouble to do the work, positive results are forthcoming, and that the landscape of the literary evidence, far from being one of randomly-scattered debris, in fact often coheres in remarkable ways. A good example of such findings would be some of Michael Cook’s own fruitful recent studies in the literary sources in two essays of his already discussed here. It is not his confirmation of some elements of the traditional account of the standard Qurʾān that I wish to highlight here, noteworthy as it may be, but rather his demonstration that we can learn from the study of the literary sources.

That’s probably all for now. If you have questions, criticism or comments please do not hesitate to tell me.

Bibliography:

The primary sources of the discussion on the Sana’a manuscripts are the works of Behnam Sadeghi, Mohsen Goudarzi and Uwe Bergmann who are currently the only ones who have, to my knowledge, analysed the manuscripts to any conclusive detail. Their work is found in the following journal articles: San’a’I and the Origins of the Qur’an (shortened Sana’a’I here) The Codex of a Companion of the Prophet and the Qurʾān of the Prophet (shortened ‘The Codex’ here – picture taken from this document).

My own comments have been colored in red.

[1] أَخْبَرَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ سَلَمَةَ، وَالْحَارِثُ بْنُ مِسْكِينٍ، قِرَاءَةً عَلَيْهِ وَأَنَا أَسْمَعُ، – وَاللَّفْظُ لَهُ – عَنِ ابْنِ الْقَاسِمِ، قَالَ حَدَّثَنِي مَالِكٌ، عَنِ ابْنِ شِهَابٍ، عَنْ عُرْوَةَ بْنِ الزُّبَيْرِ، عَنْ عَبْدِ الرَّحْمَنِ بْنِ عَبْدٍ الْقَارِيِّ، قَالَ سَمِعْتُ عُمَرَ بْنَ الْخَطَّابِ، – رضى الله عنه – يَقُولُ سَمِعْتُ هِشَامَ بْنَ حَكِيمٍ، يَقْرَأُ سُورَةَ الْفُرْقَانِ عَلَى غَيْرِ مَا أَقْرَؤُهَا عَلَيْهِ وَكَانَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم أَقْرَأَنِيهَا فَكِدْتُ أَنْ أَعْجَلَ عَلَيْهِ ثُمَّ أَمْهَلْتُهُ حَتَّى انْصَرَفَ ثُمَّ لَبَّبْتُهُ بِرِدَائِهِ فَجِئْتُ بِهِ إِلَى رَسُولِ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم فَقُلْتُ يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ إِنِّي سَمِعْتُ هَذَا يَقْرَأُ سُورَةَ الْفُرْقَانِ عَلَى غَيْرِ مَا أَقْرَأْتَنِيهَا . فَقَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” اقْرَأْ ” . فَقَرَأَ الْقِرَاءَةَ الَّتِي سَمِعْتُهُ يَقْرَأُ فَقَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” هَكَذَا أُنْزِلَتْ ” . ثُمَّ قَالَ لِي ” اقْرَأْ ” . فَقَرَأْتُ فَقَالَ ” هَكَذَا أُنْزِلَتْ إِنَّ هَذَا الْقُرْآنَ أُنْزِلَ عَلَى سَبْعَةِ أَحْرُفٍ { فَاقْرَءُوا مَا تَيَسَّرَ مِنْهُ } ” .

[2] See History of the Qur’anic Text, Mustafa Al-A’zami, Chapter 11.

[3] Hunting for the Word of God. Sami Ameri. Kindle Location 3000 onward.

[4] The Codex, p.363: “The upper text is definitely ʿUtmānic. It exhibits the kinds and magnitude of deviation from the standard text that typically accumulated in the course of written transmission. It is to the ʿUtmānic textual tradition and the place of the upper text in it that I now turn.” This is, of course, speaking about the skeletal text (ie. the Arabic writing without the dots is the same: neither the upper or lower text uses dots on its script). Another variant in the upper text discussed in the paper is where certain verses end. For example, is “Alif, Lam, Meem” a verse by itself or a part of “dhaalika -lkitaaba la rayba feeh…” in Surah Baqarah? This was omitted for brevity, please see “The Codex” if you are interested in learning more.

[5] Ibid, p.416.

[6] Ibid, p.371

[7] History of the Qur’anic Text, Edition 1. Mustafa Al-Azami. p.90

[8] Ibid, p.93

[9] The Codex, p.354

[10] Ibid. p.353

[11] Sana’a’I. p 20.

[12] See: History of the Qur’anic Text. Mustafa Al-Azami.

[13] Hunting for the Word of God. Sami Ameri. “How then can one explain the presence of this tiny number of readings which do not belong to the ten legitimate readings? The answer is as follows: They are completely, or partially, authentic, which would also not throw any doubt on the authenticity of these ten readings, because they constitute “extra readings” and not “competing readings.” Surely today no one can prove the authenticity of these “variants,” because all that is known is that these manuscripts show readings known about in the earliest centuries. It cannot be proven that they can be traced back to the Prophet. What is apparent is that the ten legitimate readings do not contain all of the original readings,{549} but only parts of the original readings,{550} because, as shown before, the Muslim nation was not commanded to keep all of the authentic readings. Though Ameri speaks of the variants that the Muslim literary sources and not the manuscript reports, the case is exactly the same.

[14] James White’s debate “Was the #Quran Reliably Transmitted from the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him)?” is an example of this.