Introduction

The Qur’an during the Prophet’s time

Say (O Muhammad) Rūh-ul-Qudus [The Holy Spirit] has brought it (the Qur’an) down from your Lord with truth, that it may make firm and strengthen (the faith of) those who believe and as a guidance and glad tidings to those who have submitted (to Allah as Muslims).11

Did the Prophet ﷺ teach multiple readings?

In order for the Muslims to read the Qur’an easily, the Prophet was commanded to teach the Qur’an in accordance with people’s dialects…and if everyone was to abandon their dialect and what they were accustomed to speaking as a child, as a youth and in their old age, this would have imposed great difficulty and hardship on them…Thus, Allah intended for them ease by allowing some flexibility in the language in the multiplicity of readings.21

I heard Hishām ibn Ḥakīm reciting Sūrah Al-Furqān during the lifetime of Allah's messenger. I listened to his recitation and noticed that he recited in several different ways which the Prophet had not taught me. I was about to jump over him during his prayer, but I was able to contain myself, and when he had completed his prayer, I put his upper garment around his neck and seized him by it and said, “Who taught you this Sūrah which I heard you reciting?” He replied, “The Prophet taught it to me.” I said, “You are wrong, for the Prophet has taught it to me in a different way from yours.”

So I took him to Allah’s Messenger and said “O Messenger of Allah, I heard this individual reciting Sūrah Al-Furqān in a way that you did not teach me, and you have taught me Sūrah Al-Furqān.”

The Prophet said, “O Hishām, recite!” So he recited in the same way as I heard him recite it before. On that Allah's Messenger ﷺ said, “It was revealed to be recited in this way.” Then Allah's Messenger ﷺ said, “Recite, O ʿUmar!” So I recited it as he had taught me. Allah's Messenger ﷺ then said, “It was revealed to be recited in this way.” Allah’s Apostle added, “This Qur’an has been revealed to be recited in seven different aḥruf, so recite it whichever way is easier for you.”22

The nature of the aḥruf

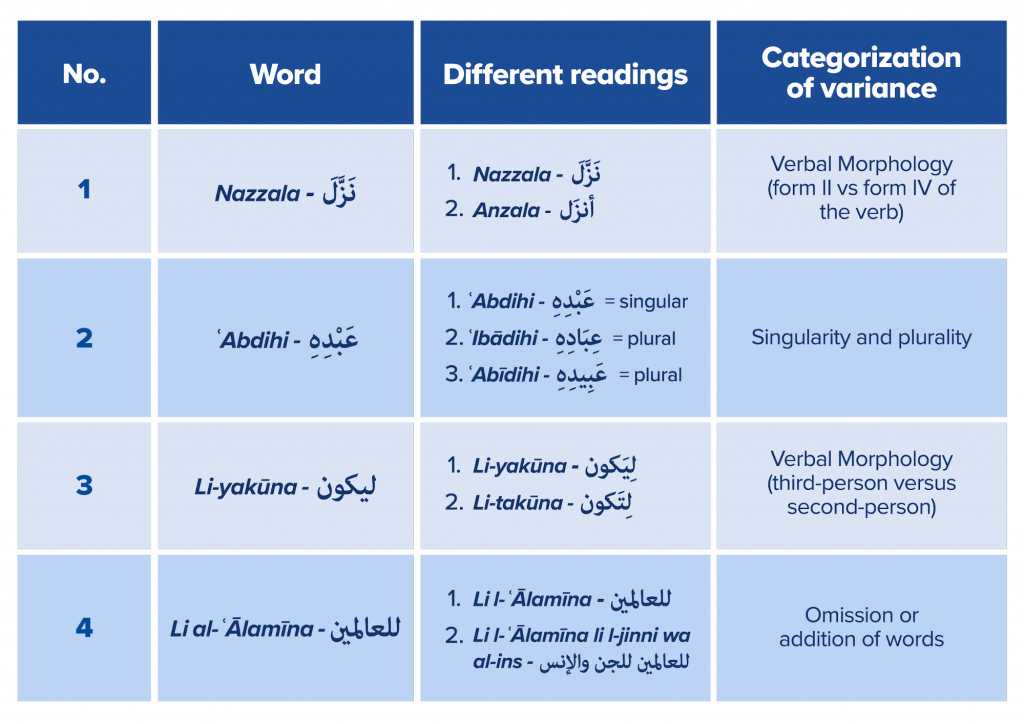

- Singularity, duality, plurality, masculinity, and femininity.

- Taṣrīf al-Afʿāl (Verbal Morphology)—verb tense, form, grammatical person.

- Iʿrāb (grammatical case endings).

- Omission, substitution, or addition of words.

- Word order.

- Ibdāl (alternation between two consonants or between words).

Codices of companions

Hudhayfah ibn al-Yamān came to ʿUthmān at the time when the people of Shām and the people of ʿIrāq were waging war to conquer Armenia and Azerbaijan. Hudhayfah was afraid of their (the people of Shām and Irāq) differences in the recitation of the Qur’an, so he said to ʿUthmān, “O chief of the Believers! Save this nation before they differ about the Book (Qur’an) as Jews and the Christians did before.” So ʿUthmān sent a message to Ḥafṣah saying, “Send us the manuscripts of the Qur’an so that we may compile the Qur’anic materials in perfect copies and return the manuscripts to you.” Ḥafṣah sent it to ʿUthmān. ʿUthmān then ordered Zayd ibn Thābit, ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr, Saʿīd ibn al-ʿĀṣ and ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Ḥārith ibn Hishām to rewrite the manuscripts in perfect copies. ʿUthmān said to the three Qurayshī men, “In case you disagree with Zayd ibn Thābit on any point in the Qur’an, then write it in the dialect of Quraysh, the Qur’an was revealed in their tongue.” They did so, and when they had written many copies, ʿUthmān returned the original manuscripts to Ḥafṣah. ʿUthmān sent to every Muslim province one copy of what they had copied, and ordered that all the other Qur’anic materials, whether written in fragmentary manuscripts or whole copies, be burnt.33

How many variant readings of companions are there that differ from the ʿUthmānic codex?

Did the Ṣahābah have muṣḥafs containing variant readings?

The divergent nature of the many ‘Muṣḥafs of Ibn Masʿūd’ that materialized after his death, with no two in agreement, shows that the wholesale ascription of these to him is erroneous, and the scholars who did so neglected to examine their sources well. Sadly the less scrupulous among antique dealers found it profitable, for the weight of a few silver pieces, to add fake Muṣḥafs of Ibn Masʿūd or Ubayy to their wares.49

Did these codices contain chapter differences?

Sometimes the author of a muṣḥaf would leave out a sūrah due to its popularity (shuhrah) and its not needing to be written down due to this popularity (i.e., it was common knowledge), as has been related about Ibn Masʿūd’s muṣḥaf not containing al-Fātiḥah. And sometimes the author of the muṣḥaf would write what he saw himself needing to include from other than the Qur’an in the same muṣḥaf as has preceded regarding al-qunūt al-ḥanafiyyah which it is reported that some of the companions included in their muṣḥaf and named sūrah al-khalʿ wa al-ḥafd.54

How do we view the variants reported from Companions?

- Abrogated ḥarf

- Abandoned ḥarf

- Non-Qur’anic tafsīr recital

Abrogated ḥarf

It is said that Zayd ibn Thābit attended the final review in which it was clarified what was abrogated and what remained.

Abū ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Sulamī said, “Zayd recited the Qur’an twice to the Prophet during the year in which he passed away, and this recitation is called the qirāʾah of Zayd because he transcribed it for the Prophet and recited it to him and witnessed al-ʿarḍah al-akhīrah, and he taught its recitation to people until he passed away. That is why Abū Bakr and ʿUmar relied upon him in its compilation and ʿUthmān appointed him in charge of writing the maṣāḥif—may God be pleased with them all.”66

Abandoned ḥarf

Non-Qur’anic recital

As for Ibn Masʿūd then much has been narrated from him including that which is not reliably established according to the people of transmission. And that which is established which differs from what we say (i.e., recite in our muṣḥaf), then it is interpreted to mean that he wrote in his muṣḥaf some rulings and tafsīr which he believed to not be Qur’an, and he did not believe that to be impermissible as he saw it as a parchment upon which to write what he willed. While ʿUthmān and the community deemed that to be prohibited lest with the passage of time it be assumed to be Qur’an. al-Māzirī said: So the disagreement goes back to a jurisprudential matter (masʾalah fiqhīyah) and that is whether it is allowed to include commentary interspersed in the muṣḥaf.86

Evaluation of the aforementioned explanations

- The reading was an innovation or fabrication.

- The reading has not been reliably transmitted.

- The reading represents the addition of explanatory words.

- The reading was abrogated in the final days of the Prophet’s life and known to be abrogated by the majority of companions, but an individual companion who was unaware may have continued to recite it as he learned it.

- The reading was actually a mistake made by a successor in his recitation but the listener thought it was a variant reading and transmitted it as such.

Critiquing a different paradigm: qirāʾah bi-l-maʿná

[O]ral literature is typically ‘multiform’ (rather than ‘uniform’), that is, what is understood by the singer or poet to be the same song or poem may be performed on different occasions with considerable minor changes, especially of the formulaic expressions of which such literature is full, although the ‘story-line’ remains the same, as does the overall form, and the singer may insist that he is singing exactly the same song or reciting exactly the same poem. In other words, there is a known message, and a known form, but each re-production of it is a fresh one which is not necessarily bound by the one before—until, that is, it is reduced to writing and the pressure builds to conform to the newly written form. But this approach is, of course, very different to that of people used to the fixed outlines of a written text (among whom we must include almost all scholars of the Qur’an, whether in the past or the present, and whether Muslim or otherwise).

[...]Now the Qur’an is not poetry, nor can we talk about it as the ‘composition’ or ‘creation’ of an individual poet or singer. It is, nevertheless, very much first and foremost an oral phenomenon which first manifested in a society in which such ‘oral transmission,’ ‘oral composition,’ ‘oral creation,’ and ‘oral performance’ of poetry was very much the norm. So we can expect it to have been experienced, in a cultural sense, rather in the same way that poetry was at that time; meaning, that a limited amount of ‘variation’ was not only accepted but also expected, if it was even noticed; it was, in a sense, built in to the very text.96

Abū Uways said, “I asked al-Zuhrī about al-taqdīm wa-al-taʾkhīr (reversing the order of words or a phrase) in Hadith and he replied, ‘This is permitted with the Qur’an so how about the Hadith? If the meaning of the Hadith is captured correctly and one does not make the impermissible permissible or make the permissible impermissible, then there is no problem and that is if the meaning is correctly captured.”97

If God, out of mercy and compassion for His creatures, revealed His Book in seven [aḥruf]—knowing that memorization is subject to slippage—making it lawful for them to recite it with different wordings as long as their differences do not distort the meaning, then it is even more appropriate that differences in the wording of texts other than the Book of God be permitted as long as the meaning is not distorted in any text that does not convey a legal ruling. Differences in wording do not distort the meaning in such cases. One of the Successors said: “I met some of the Companions of God’s Emissary, and they were united in regard to the meaning but disagreed over the wording of a certain text. I asked one of them about that and he said, ‘It is not a problem as long as the meaning is not distorted.’”101

The meaning of the hadith is that it was a concession given to them to replace words with that which gave the same or nearly the same meaning from one ḥarf to seven aḥruf. And they were not compelled to stick to one ḥarf since it was revealed upon an unlettered nation who were not accustomed to studying, repetition, or memorization of the exact wording of something, taking into consideration those who were elderly as well as those preoccupied with striving in battle and livelihood. So a concession was given to them in that. And some raised with one dialect would find it difficult to switch to another. So the qirāʾāt differed as a result of all of that. And this is proven for us by the Hadith which explains [seven aḥruf] using the examples of halumma and taʿāl, showing the permissibility of exchanging one word for its synonym. And this is also proven for us by what has been established about substituting ghafūran raḥīman in place of ʿazīzan ḥakīman using what conveys the same essential meaning without preserving the exact wording (dūna al-muḥāfaẓati ʿalá al-lafẓ). For all of that is praise of Allah, Glorified is He. This is all in regards to what the reciter can naturally pronounce. As for what is not possible for him because it is not from his dialect, then his situation is clear. And nothing of the qirāʾāt goes beyond this principle, which is exchanging a word for its synonym or a similar word that conveys the same essential meaning. Then, when the maṣāḥif were codified, those qirāʾāt that conflicted with the codified script were abandoned and what remained were those readings to which the script was amenable. Then some readings which conformed to the script became popular while the transmission of others became rare.103

The aforementioned permission (to recite in different ways) was not according to desire, meaning that everyone could exchange a word with its synonym from his dialect, rather it was necessary to adhere to what was directly heard from the Prophet, and this is indicated by the fact that both ʿUmar and Hishām said, “The Prophet recited it to me this way.” However, it is established from more than one companion that he would recite using synonyms without precedent (wa law lam yakun masmūʿan lahu). And it is for this reason that ʿUmar critiqued Ibn Masʿūd’s recitation of “attá ḥīn” to mean “ḥattá ḥīn” and he wrote to him, “Verily, the Qur’an was not revealed in the dialect of Hudhayl so teach people the recitation of Quraysh and do not teach them the recitation according to the dialect of Hudhayl.”105

Evaluation of evidences and arguments

- The seven aḥruf hadith which convey a degree of fluidity so long as the message is not altered, such as the hadith wherein the Prophet ﷺ states, “Whether you say ‘Samīʿan ʿAlīman’ (Most Hearing, Most Knowing) or ‘ʿAzīzan Ḥakīman’ (Most Mighty, Most Wise) then Allah is like that, so long as you do not conclude a verse of punishment with mercy or a verse of mercy with punishment.”109

- Reports about the reading or teaching of companions; e.g., the hadith reported from Abū al-Dardāʾ and Ibn Masʿūd about teaching a man to recite ṭaʿām al-fājir instead of ṭaʿām al-athīm.110 Anas ibn Mālik recited aṣwabu qīlan instead of aqwamu qīlan and when questioned about that, he replied that the meaning was the same.111

- Reports about the companions seemingly criticizing or denying a Qur’anic reading, which would seem to negate the supposition that they are all equally valid and all from the Prophet.112 This includes, for instance, an example of ʿĀʾishah denying one of the readings of 12:110,113 and ʿAlī denying the ʿUthmānic reading of 56:29.114

- The existence of shādhdh readings which do not conform to the ʿUthmānic muṣḥaf.

- The examples of reciters performing ijtihād based on the ʿUthmānic text or reciters who selected a reading without precedent.115

- The argument that the sheer quantity of all readings that would be traced back to the Prophet ﷺ makes it seem implausible that he could have recited them all.

As for those reports that have been transmitted concerning the permissibility of reciting Ghafūr Raḥīm in place of ʿAlīm Ḥakīm, then it is because all of that is from what has been revealed in waḥy (revelation). So if one recites that phrase in other than its correct place so long as he does not conclude a verse of punishment with a verse of mercy or a verse of mercy with a verse of punishment, then it is as if he recited the verse of one sūrah with the verse of another so he would not be sinful according to that. And the basis is that qirāʾah which was confirmed in the year the Prophet passed away after Jibrīl reviewed the Qur’an with him twice that year, and then the companions agreed upon its compilation between the covers of the muṣḥaf.118

Some of those astray may resort to such reports to cast doubts and state: whoever recites according to a reading that conforms to the meaning of a ḥarf from the Qur’an is correct so long as he does not contradict the meaning or bring forth other than what Allah intended and meant, and they use as proof this statement of Anas ibn Mālik. And this argument is an empty claim that should not be relied upon nor should the one making it be paid any attention. And that is because if one were to recite according to words that differ with the wording of the Qur’an despite approximating its meaning and general intent, then it would be permissible to recite in place of “al-ḥamdu lillāhi rabbi al-ʿālamīn” the phrase “al-shukru lil-bārī malik al-makhlūqīn.” And the flexibility in this regard would continue to increase until the entire wording of the Qur’an was nullified and replaced with that which would be a fabrication upon God and a lie upon His Messenger.126