by Siraj Islam

“(Gibson’s) evidence provides no grounds to conclude that Petra had a play in Islam. Quite in contrary, one can make a confident case that Petra has nothing to do with the emergence of Islam.”

Daniel “Dan” Gibson (b 1956) is a self-published Canadian author studying the early history of Arabia and Islam. His Quranic Geography (2011) is an attempt to examine some geographical references made in the Quran. It looks at the people of ‘Ad, the people of Thamud, the Midianites as well as Medina and Mecca. His claim that the Holy City and the birthplace of Islam is really Petra rather than Mecca1 – based upon his understanding that the earliest mosques were directed2 towards Petra – drew some interest from a small number of audience, including Muslims and non-Muslims.

For readers who are interested in or fascinated by this Mecca vs. Petra theory but haven’t gone through Dan Gibson’s actual arguments, here is a brief review of his book by A. J. Deus:

Extraordinary Claims require Extraordinary Evidence

In the book Qur’ānic Geography, the author Dan Gibson makes a case that the orientation of early mosques is evidence for Petra playing a major role for the beginnings of Islam. Until the early eighth century, he claims, they all point to Petra and from the time of the Abbasids to Mecca. In between is, what he calls, a time of confusion. In the author’s own words, his case can be summarized as following:

In the book Qur’ānic Geography, the author Dan Gibson makes a case that the orientation of early mosques is evidence for Petra playing a major role for the beginnings of Islam. Until the early eighth century, he claims, they all point to Petra and from the time of the Abbasids to Mecca. In between is, what he calls, a time of confusion. In the author’s own words, his case can be summarized as following:

“The only conclusion I come to is that Islam was founded in northern Arabia in the city of Petra. It was there that the first parts of the Qur’ān were revealed before the faithful were forced to flee to Medina. Thus, the prophet Muḥammad never visited Mecca, nor did any of the first four rightly guided caliphs. Mecca was never a centre of worship in ancient times, and was not part of the ancient trade routes in Arabia. All down through history the Arabs made pilgrimages to the holy sites in the city of Petra, which had many ancient temples and churches. It was in Petra that 350 idols were retrieved from the rubble after an earthquake and set up in a central courtyard. It was in Petra that Muḥammad directed the destruction of all the idols except one, the Black Stone. This stone remained in the Ka’ba in Petra until it was later taken by the followers of Ibn al-Zubayr deep into Arabia to the village of Mecca for safe keeping from the Ummayad armies. And today it is to this stone that Muslims face, rather than to their holy city and the qibla that Muḥammad gave them [page 379].”

These are extraordinary claims. It is surprising that their source is a scholar with a literal approach to the Bible, the Koran, and the traditions. However, since the idea of Petra playing any role in Islam is an extreme niche position, this claim requires extraordinary evidence. The author’s research appears to brake with all conventions of the Mecca-Medina narrative of emergent Islam.

In short, within the margin of error that mosques could be oriented at the time, there is no such pattern as the author claims.

The book starts with Geographical Locations in the Koran. In it, he bases a theory that the Koran is different from other ancient scriptures and early writings on the frequency of places named in scripture. I am unable to follow the logic how the word count and the number of geographical locations could lead to any other conclusion than randomness (in a non-random text construct).

Based on his numerology, he builds the history of the Arab people through the Bible. This is supposed to draw the historical path of the relevant tribes that show up at the gates to Islam. However, we have evidence that they adopted linages in Biblical locations when opportune. This is in particular important when it concerns the inheritance of the Promised Land as evidenced from the primary record. In fact, we know that linages were ‘sorted out’ under Nehemiah ben Hushiel, the supposed son of the Exilarch, who was in an alliance with Benjamin of Tiberias, Elijah bar Kobsha and Xosrov under General Shahrbaraz in 614 AD. If the actual progression is ignored in favor of a Biblical narrative, I am wondering how the author would get himself out of an impenetrable maze.

Later in the book, the author tries to reconcile the Biblical view with Muslim traditions, and he even notes that Jewish refugees had spread throughout the entire Arabian Peninsula. With that said, researchers would need to be on the lookout for attempts to reverse-engineer history.

In the author’s promised identification of the locations in the Koran, I do not find myself convinced that the interpretations by the author can be academically duplicated without a strong will to having to find any solution. Granted, the locations could be those, but there are many other theories that sound just as valid. Based on linguistic conjecture, he proposes that ‘Ad is identical with the Biblical ‘Uz. While this could well be so, I am unable to follow the academic argument. So far, academia does not understand the methodology of how the Koran has been written. Without this foundation, every attempt to define a word that is not readily understood can only lead to disputable proposals and wishful thinking. The icing of the cake is that the author is infatuated with the Koran’s Arabic words when we know that much of the original Koran had been written in Aramaic and Syriac. Since we are also void of the methodology of the Biblical construct, the author is building a sand castle upon a mountain of sand.

The author’s Biblical adherence stands in stark contrast to his own research where he writes: ‘As I listened to Arab poets recite the histories of their tribes, I realized that there was a disconnect between a) the modern names for tribes, b) tribal names during the early years of Islam and c) tribal names in antiquity. The poets could recite their tribal lines back many generations, but few of them could go farther than a thousand years, and none of them could connect with ancient groups like the Amalekites, the Midianites, or the Nabataeans, other than those directly related to the prophet Muḥammad (page 187).’ This is troublesome, because it is also a systemic mechanism of religion to reshape the collective memory. Memorizing bogus linages from kindergarten does not validate them, does it?

The author’s Biblical adherence stands in stark contrast to his own research where he writes: ‘As I listened to Arab poets recite the histories of their tribes, I realized that there was a disconnect between a) the modern names for tribes, b) tribal names during the early years of Islam and c) tribal names in antiquity. The poets could recite their tribal lines back many generations, but few of them could go farther than a thousand years, and none of them could connect with ancient groups like the Amalekites, the Midianites, or the Nabataeans, other than those directly related to the prophet Muḥammad (page 187).’ This is troublesome, because it is also a systemic mechanism of religion to reshape the collective memory. Memorizing bogus linages from kindergarten does not validate them, does it?

On the other hand, Gibson does a great job in demonstrating the primary evidence of the Nabateans. However, it should make the Biblical narrative redundant with which he had started out. Yet, he continuously attempts to reconcile the Bible with the real Nabateans. In the face of the primary evidence, this is absolutely unnecessary other than providing for the (wishful) linage background.

In his attempt to identify locations in the Koran, the author walks on a slippery slope by bringing the Khabiri together with the Children of Israel, respectively the Hebrews, for example. As with the Koran, academics have to be careful not to fall into the trap of confirming Biblical stories with archaeology when the possibility is at hand that the stories themselves have been inserted into real history or borrowed from other people’s histories. How they may be related to the Nabateans, we simply do not know. Thus, with the approach of the author, I recommend reading the Bible and taking it at face value rather than following the Biblical tour of the book.

From page 138, the author starts to engage in ‘real’ history. Based on a personal ‘opinion’, he states that Dr. John Healy was convinced that the Thamuds and the Nabateans were one and the same people. ‘They had the same names, the same gods, the same practices, and yet they wrote with different scripts.’ This rests on the idea that the Nabateans may have used two different scripts in parallel, one for (encoded secret) religious purposes (Monumental) and one for clear text proto-‘Arabic’, Safiaitic. These two scripts should have provided Gibson with a decisive clue how to approach the topic more carefully.

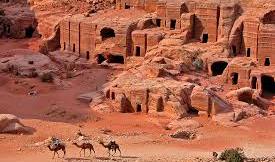

He also equates the Arabs with the Nabateans, whereas seventh century primary evidence clearly speaks of two different kinds of Arabs, those friendly with the Christians and the others, the Tayyi, not so much. Finally, the reader ends up in Petra, which is the place around which the author builds his central thesis: Petra as the focal point of early mosques. In order to demonstrate the importance of Petra, he thinks that it is one of five burial cities, whereas two annual festivals (pilgrimages) were held in Petra itself. In addition, Petra was an important gateway to the Nabatean trade routes through the desert, which they controlled (together with the Silk Road and Damascus) with access to (hidden) water holes. However, with all this, the author does not provide the foundation of why Petra would have been singled out as the mosques’ focal point, even though it may have been (at much earlier times) the capital (Rekem) of the Nabateans.

In contrary, he asserts that Medina had been the prophetic focal point (after Mecca) and that the city of the Prophet would have been the capital of the Muslims under Abu Bakr and Umar. Based on primary evidence that Gibson does not provide, this might well be the case. But that Mu’awiyah later took the Muslim capital from Medina to Damascus, as it is said, is mere fancy. During the ‘civil war’ in 685 AD, Mecca may have been destroyed and/or re-founded. All this conflicts with the primary evidence wherein the Umayyads had not only opposed proto-Islam but wherein the Prophet himself does not appear in the historical record until after 632 AD. The issue is that we are unable to draw solid conclusions when the timeline, the locations, and the people are all off. Nothing finds a solid anchor, and the unsuspecting reader risks to be exposed to mere speculation.

The book only starts to be more focused and forceful from page 221. Like others before him, Gibson notes that the Koranic geography about Mecca does neither match the present location nor was it recorded on ancient maps. But then the work of the previous 200 pages kicks in and emerges as a tunnel vision: Mecca (or Medina, perhaps) is impossible; Petra and Petra only can have been the real location of the Mother-City and the Forbidden Sanctuary as if Jerusalem would not have been a far bigger price in the eye of the Muslim conquerors. He does have a point that the Biblical narrative of Ishmael growing up in Paran, the traditional home of the Thamudic or Nabataean people in northern Arabia provides for a thousand kilometer chasm between the Bible and Islam.

The direction of prayer then turns into the main argument. Mosques were initially not oriented toward Mecca. This does not rest on some complex theory but on the simple fact that the Koran itself directs this change in prayer orientation in Sura 2. It is merely logical that early mosques could be oriented toward the Kaaba only after this decree would have been disseminated and universally understood in the same way. But so far, academia has been unable to come forth with a sensible date when this would have been written. At the least, following consensus, this should have been during Muhammad’s lifetime of the traditions, i.e. before 632 AD. Gibson, instead, asserts that this directive has been missing in early Korans that have been recovered. The author takes note of the fact that the orientation was changed much later than the traditional life of Muhammad and thinks that this must have occurred after the civil war under ’Abdallāh ibn Zubayr. He makes a case that 100% of those mosques before 725 AD, of which he could determine the orientation, pointed to Petra.

But before we continue, we must do what Gibson did not do: establish the orientation of the Great Temple of the Nabateans in Petra and also of the Kaaba itself and some of the earliest mosques that he could not determine in order to find a starting point. Also, it needs to be stated that most of the locations of the first ‘mosques’ that are mentioned in the traditions cannot be identified today. The Great Temple in Petra points straight to Baalbek and further north to the ancient city of Ebla. This would require some explanation but could be by mere chance because the orientation is also astral as were several monuments in Petra. The Kaaba, as is well established, rests on pre-Islamic foundations, and its major axis is oriented toward the Canopus. For the early mosques in Medina and China, it needs to be said that they were either built later than claimed, or they were not Muslim. No Muslim mosque could have existed in the absence of Muhammad (who appeared after 632 AD). Fustat is likely also wrongly dated, because it cannot possibly lie before Medina.

We need to establish more fundamentals that Gibson also did not deliver: how precisely were the builders able to orient mosques toward any desired location? It turns out that they were exact to roughly one degree in latitude and longitude (!), even if a building would be located 1500 km away. Thus, deviations that are much larger than one degree need to be dismissed as out of range of a desired destination.

While measuring structural orientations from satellite images is tedious but precise (+/- 0.25°), within a few days, each mosque could have been mapped out precisely by the author. For whichever reason, in a separate table that I obtained from Gibson, he merely states ‘Petra’ as direction with no measurements or deviations provided. After careful re-examination, it appears that any building that sort of looks in the direction of Petra, was taken as evidence. This includes many buildings that are as far off as 10° and more or even 30°. Within the parameters just described, not a single mosque or building on his list points to Petra with one exception in Oman that comes within 1° of Petra (built during the author’s claimed ‘time of confusion’ and attributable to mere chance).

Thus, would Gibson have been just a little bit more careful, or had his work been reviewed by an alert peer, it would have become clear that the evidence provides no grounds to conclude that Petra had a play in Islam. Quite in contrary, one can make a confident case that Petra has nothing to do with the emergence of Islam.

The picture that emerges makes it clear why a similar pattern of one focal point has not shown up long ago. The directions of these structures are fairly precise, and there is not a mistake of 2, 3, or more degrees. As the orientation of later mosques shows, they are pretty much smack on. What we could say so far (if anything) is that a) the earliest known Muslim structures were not oriented toward either Mecca or Petra, and from this follows that b) an orientation toward Petra could only confirm a non-Muslim structure.

On the other end is Gibson’s case that 100% of the mosques from the Abbasid times would be built oriented toward Mecca. However, one of the most important holy sites for the Shi’ites is the al-Askari Mosque in Samarra. This tenth century mosque is not oriented toward Mecca — the hundred-year older Great Mosque of Samarra is. Some traditions indeed suggest that not everybody had made use of the complete Koran. If Sura 2 had been missing for some, or if the related verses were missing, then the orientation of the mosques would not yet have been defined for them. Yet, that would require that they would be oriented toward the ‘old’ focal point, which with certainty is not Petra.

It is not possible to reconcile Gibson’s thesis with the realities on the ground. Neither do many early mosques have been oriented toward Petra (perhaps a few within a broader margin and perhaps by mere chance) nor has the ‘time of confusion’ ended in the middle of the eighth century.

Gibson then delves into the literary evidence, in particular the traditions, the Koran, and again the Bible. I am a little puzzled by the circumstance that the author’s theory defies tradition, but then he has no remorse in serving up questionable evidence from the traditions. Should not his case tell him that there might be something awfully odd with these beliefs that had been sorted out two hundred years after the fact? If they were able to bury Petra, what else were they able to come up with? On the other hand, the author is unable to produce even a single piece of literary evidence that would say something like Petra was the original hub. This would make for a perfect crime on a very grand scale. Something must have been left behind, anything, however little. He offers nothing at all, not even a single foundation stone that could be attributed to the earliest Muslims. After all, it is Gibson’s central thesis that the Kaaba had stood in Petra for several decades, prompting a whole chain of events that must have followed this building without leaving anything behind at all. The author asks: ‘If Petra is the first Islamic Holy City before the Black Stone was moved to Mecca, then would it not make sense that later writers would eliminate every mention of Petra?’ In religion, nothing is impossible. However, with the level of archaeological, numismatic, and literary documentation that we possess today, it seems rather unlikely that this could have been done successfully. It is one thing to insert a non-existing story into the history books or to swap timelines or locations – the level of difficulty is altogether different when it comes to removing an existing story without leaving a trace behind. But the orientations of the mosques constitute the traces, one might object. I just cannot validate this evidence. At every step along the way, I find myself faced with a religiously defended argument: do you not see this? Do you not see that? The more I read, the more it feels like faith.

Frankly, at times, I feel that the author looks down upon his audience, and he is perhaps eligible to doing so. After all, lovers of conspiracy theories with little learning will feast upon a case that sounds so fantastic that it borders to a miracle. I do agree, Mecca rises to be the focal point of the Muslims much later than the traditional view suggests. However, the case for Petra rests on no less real evidence than the one for Mecca. Academia needs hard facts, not arguments.

Finally, Gibson’s chapter about navigation and pre-Islamic poetry is informative, even excellent. In essence, it tells the reader ‘that the Arabs would have no trouble accurately determining the direction of the qibla for their mosques’ – and that is the final nail in the coffin to a theory that rests on an inexact orientation of an arbitrary selection of mosques. (Words highlighted by the author S. I.)

A. J. Deus is specialized in history in economics of organized religion. He is also an expert in religious frauds.

Further reading:

***********************************

Note 1

Among many other facts, there are three simple facts that contradict the claim about Islam’s Nabatean origins: 1. The Quran’s mention of Mecca in relation to its own story. 2. The presence of 200 Amharic and Ethiopic loanwords in the Quran. 3. Quranic references to pagans’ idol worship and animal sacrifice.

1. Regarding the quranic evidence, the fact that the Quran names Mecca just once (48:24) may look inadequate when compared with the New Testament’s naming Jerusalem, for example, almost 180 times. However, the two scriptures are radically different books. By way of comparison, the Quran names only a few contemporary geographic locations and none more than a couple of times, while the New Testament names many towns and other geographic features multiple times. Likewise, the Quran names Muhammad just four times, while the New Testament uses the name Jesus well over a thousand times. Thus, the important point with reference to the Quran’s naming of Mecca is that it names it in relation to its own story, whereas al-Raqim (18:9, Petra?) is mentioned only in relation to a historical event. And there’s nothing about that mention to suggest that al-Raqim is in the vicinity of Muhammad’s hearers.

2. Significant linguistic borrowing suggests extensive cross-cultural interaction. When goods and ideas are exchanged, words often are as well. Cultural dominance may play into linguistic borrowing also, and Ethiopia ruled the Hijaz for a time during the 6th century. If the Quran’s early suras were addressed to the inhabitants of Petra, one might expect more Coptic than Amharic and Ethiopic loanwords since Nabatea was much closer culturally to Egypt than to Ethiopia. Yet Amharic and Ethiopic words in the Quran stand in a 20:1 ratio to Coptic words. While this simple numerical comparison is not conclusive, it certainly raises questions.

3. Regarding pagan practices, the Byzantines had forbidden both idol worship and animal sacrifice long before Muhammad’s time – including in their province of Arabia Petraea. Yet the Quran repeatedly refers to idolatry as a contemporary practice, calling the unbelievers to forsake their idols, which they look to for protection (e.g., Q 2:256-57, 16:36). G.R. Hawting has argued that Muhammad challenged only the “spiritual idolatry” of retrograde monotheists. But in its listing of proscribed foods, Q 5:3 says, “Forbidden to you are carrion, blood, pork… whatever has been sacrificed to idols.” This was clearly pagan idolatry, which points to a region like Arabia’s Hijaz, beyond the bounds of the Byzantine Empire. Q 22:30 also warns against contamination by “the filth of idols” (awathan). The Quran also condemns “sacrificial stones” and the meat sacrificed on them (Q 5:3, 5:90). But since sacrifice had long ceased to be part of Jewish practice and was never practiced by Christians, this can only relate to idolatrous practice. The Quran repeatedly bans “that on which any name other than God has been invoked” (e.g., Q 2:173, 5:3). Likewise, Abraham is repeatedly presented as the prophetic hero who challenged his people’s idolatry (e.g., Q 26:69-102) as Muhammad is now doing. How does such paganism square with the Quran’s mention of the idolaters’ belief that God (Allah) created the world? In fact, it’s consonant with what we know of widespread polytheistic belief in a High God. Q 6:136 even describes the pagans as offering some portion of their produce to God, while other passages present them as ascribing offspring to God, swearing by God and even praying to God when in distress (e.g., 6:63-64, 6:109, 16:57). Not only is this quranic picture of pre-Islamic paganism consonant with polytheistic belief in a High God. It’s also generally consistent with both pre-Islamic poetry and the Book of Idols. And epigraphic evidence from both Palmyra and South Arabia attests to the pre-Islamic Arabs’ ascription of daughters to God. To sum up, the Quran condemns not adulterated monotheism, but rather literal idolatrous polytheism, something that had by the early seventh century been long forbidden in Byzantine Nabatea.

Thus, the Quran’s mention of Mecca, its Ethiopic loanwords, and its references to idolatrous practice all make the Hijaz a location more likely for Islam’s emergence than Nabatea. Source: https://understandingislam.today/is-mecca-or-petra-islams-true-birthplace/

Note 2

“The Qibla Of Early Mosques: Jerusalem Or Makkah?”, a study in Islamic Awareness, concludes:

“It was claimed by Crone, Cook and Smith that the early mosques pointed towards an unnamed sanctuary in northern Arabia or even close vicinity of Jerusalem. However, a closer analysis using the modern tools available to us show that the qiblas of early mosques were oriented towards astronomical alignments; winter sunrise of mosque in Egypt and winter sunsets for mosques in Iraq. It was shown conclusively that the early mosques do not point at northern Arabia or even close vicinity of Jerusalem. We also added the study of 12 early mosques in Negev highlands to support our conclusions.

In the early centuries of Islam, Muslim did not have tools to determine the qibla with precision. Only from third century onwards mathematical solutions for determining qibla were available; even then their use was not widespread. The folk astronomy retained its strength as suggested by various mosques in Cairo, Cordova and Samarqand. This gave rise to various directions of qibla, sometimes way off from the true direction.” See https://www.islamic-awareness.org/history/islam/dome_of_the_rock/qibla

-------------------------

Here are a few related links with a range of perspectives: